Goodbye, My Sweet Cody Boy

Originally published in the Pagosa Daily Post, on April 25, 2012.

This is a story about a dog, a disease, and a drug.

My beloved dog Cody — short for Buffalo Bill Cody — was doomed to live a short life. He didn’t know it. I didn’t know it. You see, Cody was born with idiopathic (inherited) epilepsy, but was symptom free the first four years of his life.

You probably know of a dog that has epilepsy (or has died from epilepsy), because this insidious disorder has become far too common in man’s best friend.

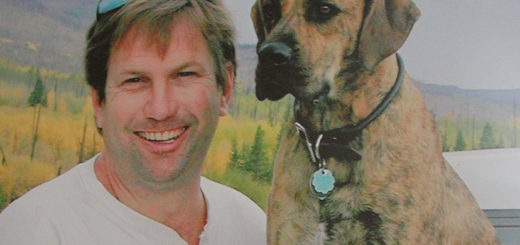

I adopted Cody from the Humane Society of Pagosa Springs (Colorado) when he was about eight months old — a skinny, matted, intact stray picked up by animal control on July 4, 2006. Cody was a sweet and smart boy from the start. He walked easily on a lead, and kept close when free. Of course he made his way to sleeping on my bed, and, at an eventual 75 pounds, took up most of the room when he stretched out.

He was a wonderful travel companion on trips between San Diego and Pagosa.

Cody was also an extraordinarily athletic and beautiful dog — for a mutt. Every day, on our walks, strangers complimented him and asked me his breed, but I had no idea. I was also curious, so I decided to do a DNA test on Cody. The results: 1/4 Golden Retriever, 1/8 Australian Shepherd, and 1/8 Akita — with the other half “unknown”.

As I found out later, Golden Retrievers are one of the breeds predisposed to epilepsy.

For fun, Cody and I tried out a recreational agility class in San Diego. He was the class standout as he enthusiastically mastered each piece of equipment (jumps, hoops, tunnels, dog walk, A-frame, weave poles). After the last class, the trainer took me aside and told me that Cody had the makings of a competitive agility dog — he was intelligent, agile, fearless, and wanted to please me — and she suggested that I consider agility training for him.

Soon after, we enrolled in regular agility classes at the Agility Club of San Diego. Cody was so excited to learn agility and to be around all the dogs in our class that he was a handful while waiting to run the course, but perfectly focused when it was his turn. We had fun. Agility training is one of the most bonding activities a dog and his owner can share.

Cody had his first seizure the morning of December 26, 2009. It’s terrifying to witness your (up until that moment) perfectly healthy, athletic, and happy dog’s first seizure. An unconscious Cody lay on the floor with eyes rolling back, vocalizing, teeth gnashing, foaming at the mouth, head thrashing, feet paddling, laying in his urine. It was a classic tonic-clonic, or grand mal, seizure.

Cody’s second seizure came some months later. Then another, and another, with the time interval between seizure events shortening. So our vet prescribed phenobarbital — the most common drug used to control canine seizures. Phenobarb (nick name) helps to control the duration and number of seizures, but doesn’t stop them entirely. The goal is control, not elimination of seizures.

Canine idiopathic epilepsy (IE) is an inherited disorder with onset occurring later in life. Although a great deal of genetic research has been devoted to discovering the cause of IE, it still remains a mystery. In fact, it is widely believed that different breeds have different genetic traits that lead to epilepsy, and that each breed must be researched separately — but thus far, nothing definitive has been found in the genetic analyses of dogs with epilepsy.

Until the causal relationship between genetic makeup and epilepsy is isolated, a genetic test for epilepsy cannot be developed.

We also know there are IE carriers who are symptom-free but may produce offspring that develop epilepsy or are carriers of epilepsy to future generations of puppies. Further complicating the issue, some “reputable” breeders are in denial that they are breeding and producing dogs with IE or carriers of IE. Instead of submitting blood samples to the research labs that are trying to isolate the genetic characteristics of IE, they hide the problem and thereby propagate it. Thus epilepsy has become prevalent in man’s best friend, and heartbreaking for those of us who are ambushed by this horrendous disease.

In October, 2011, Cody had his first cluster seizure event — multiple seizures spread out over three days. After consulting our vet, I increased Cody’s phenobarbital dosage. But Cody continued to have cluster seizures anyway. He always had three seizures in the cluster, invariably in the middle of the night. By this time, Cody had been forbidden from sleeping in my bed because he lost control of his bodily functions during a seizure; he was demoted to sleeping in his crate in my living room.

The ungodly moan that signaled the beginning of each seizure would always wake me. My adrenaline pumping, I would run downstairs to hold Cody, get the rags to clean him up, and walk him around the living room and dining room on a leash. There was a long period of panicked confusion after he came out of the tonic-clonic portion of the seizure; he would stumble around as though he were blind, banging into furniture and walls, and knocking over anything in his way. This scenario would repeat three times during his cluster seizures. It exhausted both of us. My washing machine would run non-stop, washing rags and his crate bedding and blankets.

As Cody’s seizures occurred with greater frequency, his phenobarbital dosage was increased. Periodically Cody would have his phenobarb blood serum level checked; his liver and kidney function was also monitored. The lab work always came back “within normal ranges”.

But something else was going on that I, in retrospect, didn’t pay enough attention to. At some point along our journey with epilepsy, Cody began exhibiting unusual behaviors, such as eating unusual items, and paranoia. The old Cody never took food off my kitchen counter or dining table. But now he was on a never ending search for something — anything — to satisfy a seemingly insatiable hunger. He ate a part of a ceramic plate. He ate a plastic cutting board. He ate part of a sponge, and a corner of a dustmop. He would even lick dust off the floor. He would pull unused tissues out of the Kleenex box and devour them. All waste baskets had to be moved to four feet off the floor, or he would eat their contents.

If I allowed him to walk off-leash, Cody would suddenly rush off, and I’d find him munching on decorative landscape bark, or dirt, or old, dried up animal bones. So I had to restrain him with a leash during our walks in the woods — a travesty for a dog that loved running free more than anything else, a dog that smiled as he ran.

And I had to lock Cody in his crate every time I left him at home alone, because he had become a scavenger in the house. I had to do it for his safety.

When Cody began exhibiting these strange behaviors after the onset of epilepsy — behavioral changes that belied a different dog from the loving companion I had once known — I assumed it was the seizures and epilepsy that were responsible. I would massage his head and say to him, “Poor Cody, you have scrambled brains.” He’d just look at me.

But after one particular conversation with our vet I realized his weird behavior might not be a result of the epilepsy, but might instead be a side-effect of the drug — phenobarbital — that was being used to control his epilepsy; the personality changes had become more extreme as we’d increased his drug dosage to control the increasing seizures.

I blamed myself for not realizing sooner that phenobarb might be the problem. Perhaps I could have done something different.

Which is worse? A brain threatened by seizures, or a brain confused by a mind-altering drug?

What about Cody’s quality of life? There was none, really, compared to what he had before the onset of idiopathic epilepsy. Cody now preferred sitting in the car all day to being with me in the house. I thought he wanted to be in the car so he wouldn’t be left behind, but now I realize he was exhibiting paranoia, and the car served as a den where he could hide from the demons that were plaguing him. Cody had become a full-time prisoner of his disease, and the drug I was treating him with.

As restrained as Cody was for his safety, he still would find something to eat that wasn’t good for him. Cody ate a 3-foot long cloth tie that had been sitting on a storage chest for months. I didn’t know he had eaten it, so I didn’t know why he was horribly ill for several days, until I noticed something coming out of his back end. I pulled on it, and out came the 3-foot tie.

Cody felt better for a few days, until he ate something else. I still have no idea what he ate, but this time he wasn’t so lucky. He couldn’t keep water or food down, and became very dehydrated. It was Easter weekend, and my vet had no staff available to x-ray him to determine if there was a blockage, although Cody did receive a injection of fluids, and a shot to stop the vomiting.

By Easter Sunday, Cody was refusing sips of water. His nose was bone dry. He would stand up and then lay down to readjust his pain. He wanted to be in his crate, so I sat next to his crate and watched and talked to him, sickened that he was suffering. He was dying; I was pretty sure of that.

Monday, the day after Easter, we went to the vets, and confirmed the worse with an x-ray. Something was inextricably entangled in his intestines.

It was time to put him out of his pain.

Earlier I wrote, “this time Cody wasn’t so lucky.” But maybe he was, because epilepsy and its treatment, phenobarbital, had already robbed him of the life he led his first four years as my intelligent, joyful, and loving companion. Now he was a dog mentally possessed and physically imprisoned by the drug and the disease. It was time to free him.

Cody was given a sedative. I stroked his head as he let go of his suffering and relaxed into his last sleep. “Cody’s a good boy. Cody’s a good boy…”

I miss you terribly, my sweet Cody boy.

You can learn more about canine idiopathic epilepsy at this excellent website, www.canine-epilepsy.com